The case for James Whitty. Sept 2001

Author unknown

In this very well written piece the author questions

the vilification of James Whitty who has been described as Ned Kelly's arch

enemy because he caused Kelly to become known as a horse and cattle

thief in the district. If the truth be known, Kelly's self professed

thievery could be seen as a prank following a 'blame it on the Kellys'

after Whitty's bull went missing.

This following document will expose the many

facts, one of which was, 'they were all as bad as each other' when it

came to horse and cattle stealing!, but as history is written

by the winners, Ned Kelly's reputation was further tarnished to perhaps

a

point of no return that infuriated Kelly, so 'he would give them

something to talk about' if nothing else. The whole affair was nothing

more than a feud to do with a class divides between the British and Irishmen

who were either Catholic, or Protestant - the ruling classes.

The following 3 pages of 19 a thesis document was given to me around ten years ago by a descendant of a pioneering

family that settled in the Oxley plains north of the King River valley

but

south of Wangaratta.

The author remains unknown because the title page was missing, and

presents the facts exonerating James Whitty from being depicted in popular Kelly

books as a nasty piece of work. Obviously the author felt determined

enough to set the record straight.

To the author, I apologise for taking the liberty to publish your

interesting document without knowing your name, perhaps someone will

recognise the work and let me know if it was ever published, where and

by whom.

Bill

|

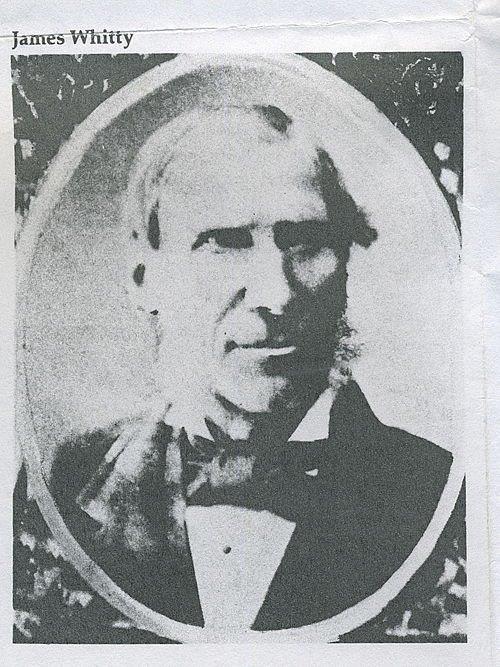

September 8, 2001 Page 2 THE CASE FOR JAMES WHITTY Who was James Whitty? One view likely to be exposed on the big screen in the near future is that James Whitty was the man who set Ned Kelly on a mad career of crime. The historical reality is much more difficult to uncover. Most of the "evidence" against Whitty circumstantial and the "facts" are skeletal, as shown in Attachment A, An extreme view is that James Whitty was a besotted farmer who got rich with the help of his Tipperary-born wife, by getting the best of a bargain with The Devil. That is how eminent Australian author, Peter Carey, characterises James Whitty is his latest novel, the so-called ‘True History of the Kelly Gang.' At least Carey has the grace to add a note describing the encounter as "fanciful". But his portrayal of Whitty is just as jaundiced throughout the book. That is an outcome of Carey's dependence on TV scriptwriter and local historian, Ian Jones, to whom Carey says he turned "when I was lost or bewildered or simply forgetful of the facts". According to Jones, Ned Kelly went bad because James Whitty and others spread lies about him. Ned did not steal Whitty's bull, nor Whitty's calves, although later he did steal a lot of horses, including Whitty's, just to give them all something to talk about. Jones believes all this because Ned says so and Jones' faith in Ned is as great as the "almost boundless" faith he says Ned had in his fellow-man. So, over a decade or so, Jones has constructed a caricature of Whitty that may be just as fanciful as the Carey version. Jones asserts that Whitty was "a dour and implacable glazier who led the King Valley squatters against the battling cocky fanners", and, Ned Kelly's "old enemy... leading light of the King Valley squatters". When making those observations in his 1992 book, The Friendship That destroyed Ned Kelly, Jones provides no authenticating source beyond Kelly's Cameron and Jerilderie letters. More recently, Jones has argued a different case, telling a Nightline audience on 9 April 2001 that "stupid" actions by the police "catapulted the Kelly outbreak into a rebellion, because at that point Ned had to act on behalf of a whole class of people in the north-east." But in his 1995 master work, Ned Kelly, A Short Life, Jones tries to sustain a different line— that untrue accusations by James Whitty and his associates set Kelly on the path that led inexorably to Stringybark Creek, Glenrowan and the gallows. The line wavers as Jones the historian battles with Jones the TV producer and script writer. The first difficulty is that Ned Kelly's perverse viewpoint as expressed in the Cameron and Jerilderie letters remains Jones primary source. The greater difficulty is that Jones accepts at face value the three claims Ned Kelly makes. First, Ned say, he turns to large-scale stock theft because he is tired of false accusations made by Whitty and others and decides to give them something to talk about. Unlike Jones, an earlier writer Frank Clune wisely dismisses Ned's claim as "self-deception". Second, Ned says, that Whitty, along with the Byrne family, had taken all the best land in the King Valley and, not content with that were greedily impounding stock that happened to stray from the paddocks of "poor" owners. Third, Ned says, Constable Thomas Farrell, brother to James Whitty's son-in-law, John Farrell, stole a horse from Ned's father-in-law, George King, and kept it in one of Whitty's or Farrell's paddocks until he left the police force. Jones adds a little substance to this raw material by drawing circumstantial evidence, mainly from Entries in the Police Gazette and advertisements or other articles, mainly from the Wangaratta Despatch and the Ovens and Murray Advertiser. Otherwise, Jones view of Ned's relationship with James Whitty is justified by some undisclosed research summarised in a monograph by Jones partner, Bronwyn Binns, and two letters from a descendant of James Whitty's brother, Patrick" The detail available from contemporary press articles inspired Jones to flesh out the "confrontation" between Kelly and Whitty at Moyhu races on 28 February 1877. His dramatisation is at least the equal of Carey's more recent effort and of Max Brown's 1947 version "".Ned is there to deny having stolen Whitty's bull. Jones has Ned striding past a banjo-strumming Negro minstrel and a lady spinning her Wheel of Fortune, his "alexandrite" eyes flashing as "the figure of stern authority", James Whitty-

September 8, 2001 Page 3

Such

dramatisations may well be within the current bounds of scholarship but

some of Jones' fictional embellishments are more dubious. At the time of

the Moyhu race-course confrontation, for example, Jones describes Whitty

as "now 62, a Dickensian figure of stern authority with his starched

collar, rawboned face and grey side-whiskers. Seemingly all good stuff

—except that the only factual basis for the description would appear to

be Jones "interpretation" of the photograph of James Whitty that is

displayed in the Burke Museum, Beechworth, as part of a montage of

district pioneers. It would be too tedious to go through a complex text in any further detail but it should be clear from the examples above that to Suit his own purposes Jones has fabricated a malign image of James Whitty. Needing to sustain his thesis of a class struggle between "squatters" and selectors, of a heroic rebellion by the oppressed against their oppressors, scriptwriter Jones needs the personification of Whitty as arch-enemy, as super-villain as anti-hero to match his hero, Ned. The trouble is that some of the known facts about James Whitty refuse to fit the role in which he is cast. Jones must have been dismayed when he obtained detail about the formation of the Stock Protection League. Far from being "the leading light", Whitty was no more than a member of the group that convened the inaugural meeting and was elected as a committee member. Jones seeks to explain this away by claiming that as 'Whitty, as usual, adopted a low profile”(xi) just as elsewhere he claims Whitty was a "grey eminence", In fact, as usual, James Whitty took his lead from Andrew Byrne who not only convened the inaugural meeting of the Stock Protection League but was elected president. Byrne, rather than Whitty could fairly claim to be the leading light among members who included John Evans as vice-president, William Dale as treasurer, RR. Tilt as paid secretary, a committee comprising A. Tone, John Brincombe, E.Batchelor, T.Smith, A.Clarke, J.Reid, A.Jeffiay (or more likely Jeffrey), Patrick Byrne and membership comprising Henry Langtree, Rowland Vincent, W.Baird, W.Dinning, F. G.Docker, J.RDocker, someone called French, John Reid, John Webster, William Orr, W.Sinclair, J.Kaine and Benjamin Evans!` (xii)

September 8, 2001 Page 4 Any of these pioneers along with the Faithfulls, the Clarks, the Chisholms, the Mackays and many others could have served Jones as representatives of the "squatter" class. Instead, because Ned Kelly named Whitty and exaggerated the consequences of a brief exchange at either Moyhu or Oxley races, Jones makes Whitty his stereotype of "oppression". The Whitty of-Jones imagination is a caricature worthy of the masterful Dickens from whom Jones draws acknowledged inspiration. A more sensible view would be to see Whitty as a victim as well as a beneficiary of the inequities arising from land distribution in early Victoria.

None of this matters if we want only larger-than-life myths and legends

or moral tales of haves and have-note of the righteous poor battling the

oppression of the undeserving rich. It matters only if we want the

truth. As historian Andrew McDermott said of Jones' view of Ned Kelly:

"If Ned Kelly had not lived we would not have one of the most precious

icons that we now have to worship....that is quite different from the

historical reality that took place". The same can be said of Jones' view

of James Whitty and more so of Peter Carey's fanciful creation.. |

The case for

James Whitty - list of facts -table-

sources click on page links below

Pages

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

If copied to other publications please reference this

source -

http://www.denheldid.com/twohuts/the-case-for-james-whitty.htm

These 'Two huts' pages are not for profit but copyright W.Denheld. Jan 2015

Reproduced by Denheld but the author owns copyright dated Sept 2001

Since

the photographs for the montage were collected some years after James

Whitty's death, it is not possible to say when the photograph was taken

or whether he looked more or less "Dickensian" than his contemporaries.

Jones likes the word "Dickensian": a Murray Valley farmer who befriends

the Kelly outlaws and obtains first-hand evidence of Ned's "obsession"

with Whitty is Dickensian simply because his name is "Gideon Margery “

Since

the photographs for the montage were collected some years after James

Whitty's death, it is not possible to say when the photograph was taken

or whether he looked more or less "Dickensian" than his contemporaries.

Jones likes the word "Dickensian": a Murray Valley farmer who befriends

the Kelly outlaws and obtains first-hand evidence of Ned's "obsession"

with Whitty is Dickensian simply because his name is "Gideon Margery “